CIM MBA Director Christiana Charalambidou discusses the understudied phenomenon of over-education in Cyprus, focusing on the firm perspective

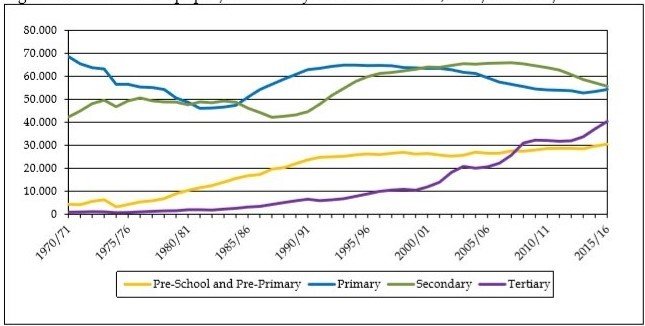

Cyprus is a country characterised by a remarkably strong demand for higher education. Due to its small-sized economy, it relies on its human capital as a key factor in production making the quality of these resources vital for the country’s economic growth. Just like other industrialised countries, Cyprus has also experienced growing levels of educational attainment during the past decades. More specifically and as demonstrated by Figure 1 below, the number of secondary school graduates who choose to pursue further studies has been following an upward trend, in part due to a number of reforms that aimed to promote higher education over the past decades as well as increased expenditure on education by the government. From the student perspective, the high demand for tertiary education in Cyprus has been associated with the desire of students to improve their employment prospects in the island’s small-sized labour market (Menon, 1998).

Enrolments of pupils/students by level of education, 1970/71-2015/16 (Source)

However, employment and career opportunities for young graduates are often limited due to the country’s small-sized economy and the great number of university graduates. When the labour market fails to absorb the surge in the supply of highly educated workers in jobs commensurate with their education, then a share of these workers ends up in over-education, a situation whereby an individual’s level of education exceeds the educational requirements for one’s job. As demonstrated by Table 1 below, the rate of over-education in Cyprus stands at 19.8%, which is above the EU average of 13.3% and ranks third in terms of the highest over-education level behind Spain and Ireland.

| Country | Over-education (%) |

| Austria | 13.4 |

| Belgium | 13.4 |

| Cyprus | 19.8 |

| Czech Republic | 6.8 |

| Denmark | 18.2 |

| Estonia | 17.9 |

| Finland | 10.1 |

| France | 9.9 |

| Germany | 12.8 |

| Ireland | 22.2 |

| Italy | 16.7 |

| Netherlands | 12.5 |

| Poland | 7.1 |

| Slovak Republic | 6.1 |

| Spain | 24.0 |

| Sweden | 10.5 |

| United Kingdom | 13.5 |

| EU average | 13.3 |

Table 1: Percentage of Individuals in Over-Education by Country

Source: Flisi et al. 2017

Over-education represents an inefficient allocation of resources as it implies an underutilisation of educational skills and has been found to have a number of negative consequences both at the individual as well as the economy level. More specifically, at the individual level over-education has been associated with lower job and life satisfaction (Tsang et al. 1991), cognitive decline (De Grip et al., 2007), poorer mental and physical health (Tsang and Levin, 1985) and lower earnings (McGuiness, 2006) while at the macroeconomic level over-education implies an over-investment in (publicly funded) education, lower overall productivity levels, lower national welfare and wasted tax revenues as individuals are equipped with non-productive education.

Nevertheless, employers may consider the oversupply of highly educated job candidates as an opportunity to hire them in jobs that require a lower level of education than what they possess. This would mean paying them less than what they would be earning in matched jobs and from the employer’s perspective gaining higher productivity and output and hence higher profits while paying less. But is this the right strategy for firms? And would the end result be higher profits, as envisaged?

The literature examining a number of dimensions of employee attidutes finds over-education to be positively associated with a number of worker behaviours that result in lower productivity. One of these behaviours, which forms the focus of the present article, is a higher propensity of over-educated workers to engage in on-the-job search (i.e. look for another job while employed) compared to their well-matched counterparts. More specifically, individuals may view a job for which they are over-educated as a stepping stone to a matched one, by for example gaining work experience or a temporary income while engaging in on-the-job search. Successful on-the-job search results in voluntary turnover which in turn can act as a correction mechanism for job match imperfections, leading to an exit from over-education and consequently a more efficient allocation of human resources.

On the other hand, and even though on-the-job search may have a vital role to play towards an efficient labour market, it can also be very expensive for the firm. Firstly, on-the-job search behaviour as a predecessor of voluntary turnover, is costly for the firm due to foregone investments in screening, hiring and training of employees who then leave the firm. What is more, on-the-job search absorbs time and energy that might be put to other, more productive, uses at the workplace. Last but not least, on-the-job search can provoke psychological processes that encourage withdrawal behaviour and decrease job and organisational commitment (Locke, 1976) leading to a productivity level below the full potential of the employee. This in turn translates into lower firm output and lower profits. It is hence obvious that on-the-job search is important as a process on its own rather than just due to its connection with job mobility and that it can impose significant costs on firms who decide to hire workers in jobs that require a lower level of education that the one they possess, irrespective of whether job search actually results in turnover.

In conclusion, it seems that even though firms may consider hiring over-educated workers as a profitable strategy, taking advantage of the over-supply of educated labour, in the medium to long- run the costs of on-the-job search and other withdrawal behaviours associated with over-educated workers will rip off any expected benefits. This means that firms will be better off not hiring over-educated workers. Given that over-education could impose a real negative productivity penalty not only on the worker but also on the firm and the economy as a whole, the creation of policies to prevent and/or reduce the level of over-education should be placed high on the political agenda. A policy example with repercussions at the firm level would be to enhance measures that facilitate the entry of young educated people directly into jobs commensurate with their education for example by subsidising part of their salaries or creating employment arrangements that enable the learning of job-specific skills and the accumulation of work experience so that graduates can enter jobs at the correct job level. Such policies give motives to firms to employ young graduates directly into matched jobs and at the same time prevent educated youth from accepting jobs for which they are over-educated as a career strategy and running the risk of being trapped in over-education as a consequence.